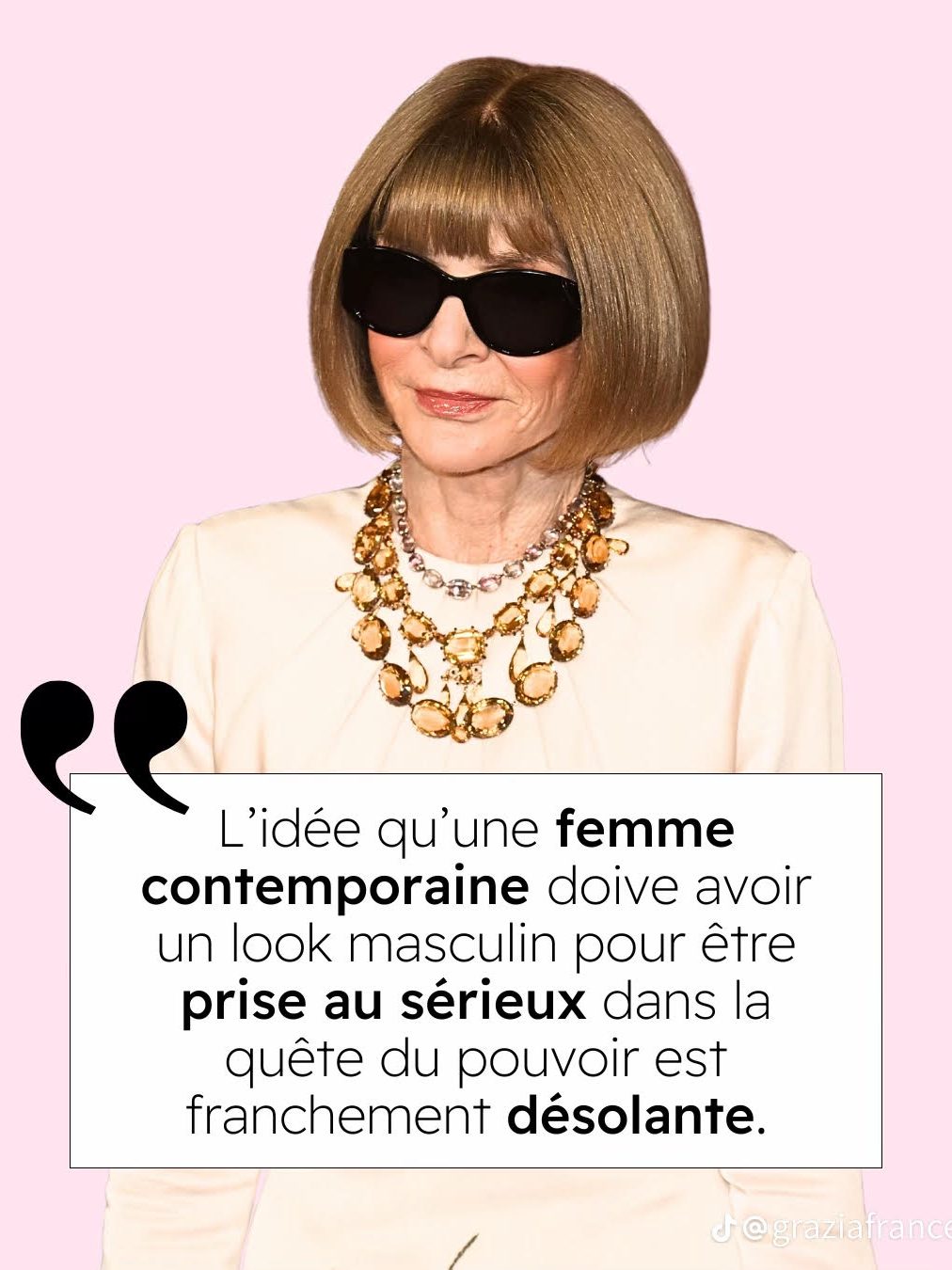

Have you ever thought about power and femininity? It’s rare, and that’s not insignificant, because power is often associated with seriousness, while femininity has always been considered frivolous and superficial. This dichotomy is an insidious way of controlling the perception of femininity and ensuring its exclusion from positions of power. The only woman to date who is universally known for not having had to choose between femininity and power is the great Anna Wintour. The departure of the editor-in-chief of US Vogue, after nearly 40 years in power, is an opportunity to take a closer look at the fashion industry and the many societal issues it raises, particularly in terms of female power and the representation of femininity.

Anna Wintour represents a very unique vision of female power. She has dominated the fashion world for nearly 40 years as editor-in-chief of US Vogue. She has also made her mark by creating the Met Gala, a cultural event that has become a symbol of the soft power she wields in this world. Anna has often been criticised for her apparent coldness and her ability to dismiss members of her team without scruples. These judgements were all the harsher because she was twice as exposed as her team. This is a reality that Anna understood well. But beyond that, she had to juggle factors that are rarely highlighted in the fashion world.

She had to evolve in a world that presented a largely feminine façade, but where the most powerful and influential positions were held by men, under the Condé Nast umbrella. This is a perfect example of how majority does not necessarily equate to power. Vogue magazine belongs to the Condé Nast group, which has been owned by the Newhouse family since the 1960s. Donald Newhouse, Robert A. Sauerberg and Charles H. Townsend are the men at the helm of this empire.

All are men whose fortunes have been built in part through magazine publishing. They are never in the spotlight, but make no mistake: their decision-making role is powerful and highly influential. It is with this set of invisible dynamics that Anna Wintour has had to juggle, always committed to high standards in terms of results and professionalism. None of these men are defined by artistic or visual creative talent, a talent often highlighted in fashion magazines. Yet they are the ones who control the budgets and a set of financial and economic parameters that Anna had to reconcile and respect during her 40-year reign.

Anna has always represented a dissonance in the perception of spaces of power. She has been elevated to the status of a powerful female figure in a world that, beneath its glitz and glamour, is in reality designed and built according to the strict rules of corporate culture. They are the real big bosses. And Anna, in order to reign for so long, has never ignored or underestimated this.

She has been criticised for her lack of warmth and apparent coldness, while forgetting that corporate culture is built on social dynamics that are both brutally and insidiously violent. This often manifests itself in very passive-aggressive actions or behaviours, which can make even the gentlest of souls intractable when confronted with these dominant dynamics.

Anna arrived confident, with a clear understanding of what she wanted and who she was. But that is not enough to provide a powerful shield against the corporate monster, in which the individual is not the master but merely a player. Sometimes cruel, sometimes brutal, this system leaves wounds even on the toughest and most prepared among us.

He is steeped in a highly structured and defined hierarchical system, leaving no room for the human and emotional aspects, but rather focusing on the rational and reasonable aspects of human nature. Thus, even Anna has had to deal with, sometimes warned, sometimes not, actions or behaviours from her superiors that must have hurt her deeply or put her to the test.

Whether it was due to coverage, reduced staff numbers, a lack of equipment or budgetary issues, it may seem trivial. However, everything is crucial, and it is the ability to coordinate and bring together several departments simultaneously that, when they work well and fit together, enables a good result. These departments must be able to meet the demands and needs of the various departments, while ensuring an excellent and profitable result.

In this world, artistic representation and visibility can only emerge from a creative and powerful combination of aesthetics and living art. This is a reality that Anna has faced throughout her reign. To secure her place and her triumph, she responded to cold, icy and passive-aggressive dynamics. Not unintentionally, but inevitably, in order to maintain and occupy a prominent position.

Known for her repeated dismissals, she simply responded with the weapons of this environment that she had learned to master. She controlled the artistic narrative with the approval of Condé Nast’s big bosses. Yes, she was cold and unfair on many occasions, but the structure of Vogue, despite its majestic appearance, is a corporate world designed and governed by men.

Anna knew and understood this because she is a woman, and because each of her decisions or actions would have had double or even triple the impact in the event of failure or fiasco. Her genius lay in her iron grip, while understanding the social and political power of every fabric, colour and symbol. These elements are capable of giving rise to a visual aesthetic, the expression of an artistic novel whose intensity and story can be read in the eyes.

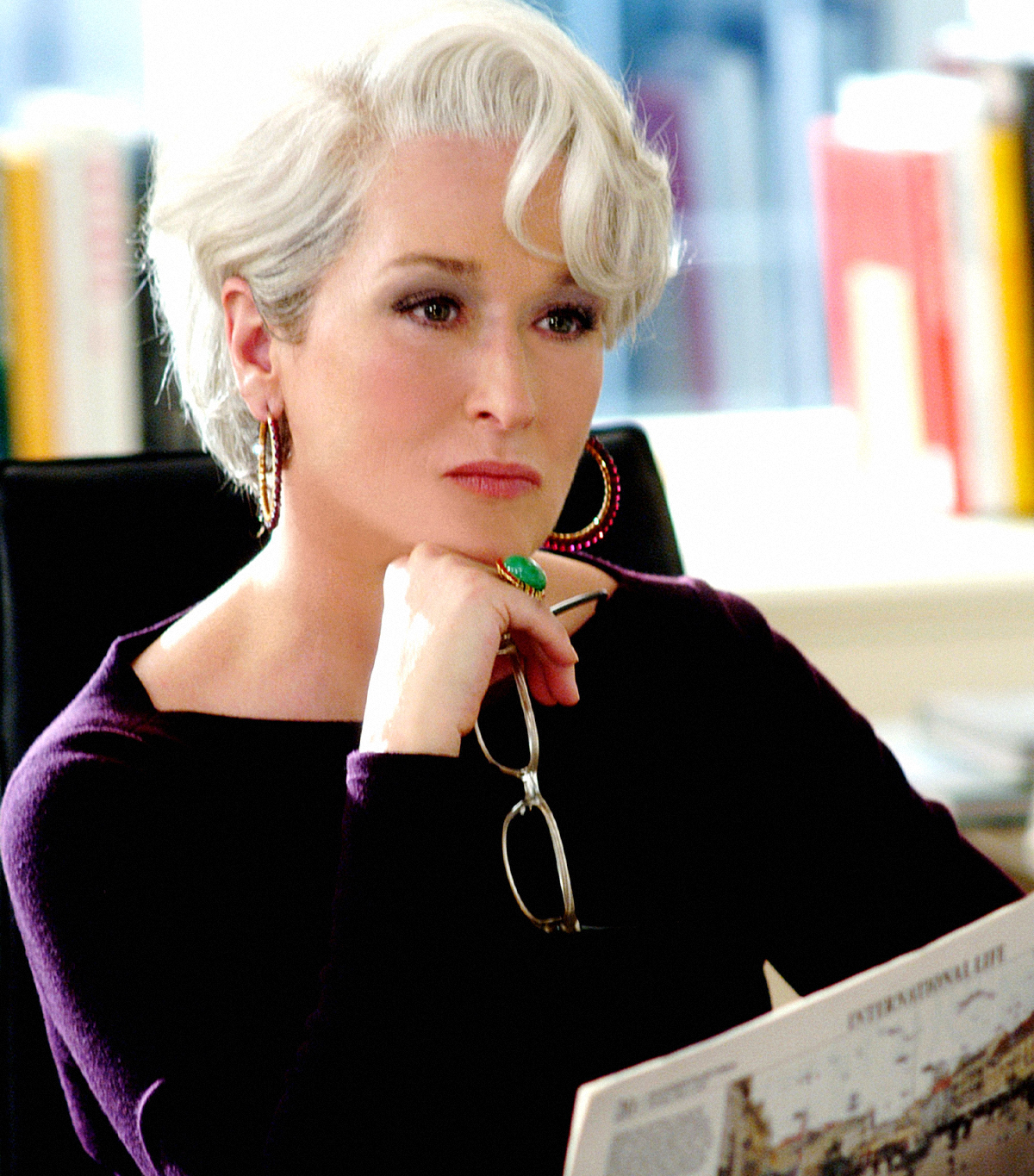

To fully understand this constant pressure and demand, what better than to talk about its pop archetype par excellence, Miranda Priestly, inspired by the last editor-in-chief of Vogue. The film The Devil Wears Prada, which has become a must-see, clearly shows the duality and challenges of publishing a fashion magazine. It reveals fashion as a social and cultural power, a means of expression and aesthetic representation for men and women.

This political language is non-verbal, but it is nonetheless a tool for controlling and perceiving individuals in social dynamics. Every aesthetic is both an affirmation of identity and a coded language, subject to the demands of corporate culture. The latter does not escape the powerful and cold Miranda, who knows how to read power and dynamics, even the most invisible ones.

One of the most memorable scenes in the film, which demonstrates Miranda’s keen analytical skills, is the one involving the blue belts. Andy laughs because she doesn’t understand the importance of the differences in shades of blue. To her, the two belts are similar. Miranda, like a fashion surgeon, dissects the story behind these two colours with a scalpel. She shows her that these nuances embody artistic, economic and human challenges.

It is then that Andy understands that, despite her degree in writing, fashion requires a lot of skills. It demands a keen sense of analysis and creativity, as well as structured, almost scientific reasoning. She feels humiliated, and rightly so: this humiliation is subtle, beneath the innocuous appearance of blue tones.

Miranda teaches Andy that even when she thinks she is free to make her own choices and is not interested in her appearance, the reality is different. What she wears has been designed by men whose creativity and decision-making power directly influence her wardrobe.

In just a few minutes, Miranda delivers a sociological analysis of fashion that overturns Andy’s personal reasoning. Andy believed she was above the influence of fashion, but in reality, she has never been free. Her choices have always been dictated by decisions made by people she doesn’t even know exist, even though their influence is significant.

Anna is often presented as a figure of female power, even hyper-feminine power. It would be incorrect to deny her strategic intelligence and the influence her achievements have had on the fashion industry. However, when it comes to the representation of female power, what is sometimes referred to as such does not always refer to the expression of power conceived, shaped or exercised according to feminine codes. It is often a woman placed under the yoke of a fundamentally masculine vision of power, an ancient, firmly entrenched vision that has simply survived the ages while retaining its own logic. This power has not changed in nature; it has only changed its face. And as long as strategic structures continue to be governed by these same foundations, the emergence of female figures at the top, however striking they may be, will not necessarily reflect a reversal of established dynamics, but rather a form of silent adaptation to their requirements.

This structural violence, although rarely named, is deeply normalised. It settles into the interstices of social and professional life, integrated as an unspoken given that must be adapted to in order to survive and advance. Often invisible and insidious, it manifests itself through implicit rules, unspoken expectations, and passive-aggressive behaviour—all mechanisms that silently shape power relations. Recognising this reality also opens the door to broader reflection: rethinking power, success, and the place of women in these spaces.

What if the power you hold lives in your femininity? Then yes, but not under the guise of a deeply masculine vision.

Laisser un commentaire